Click for Related Articles

|

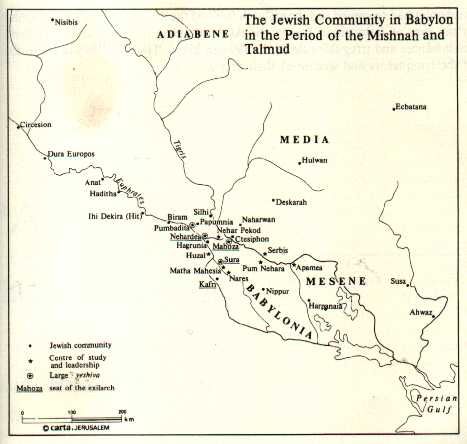

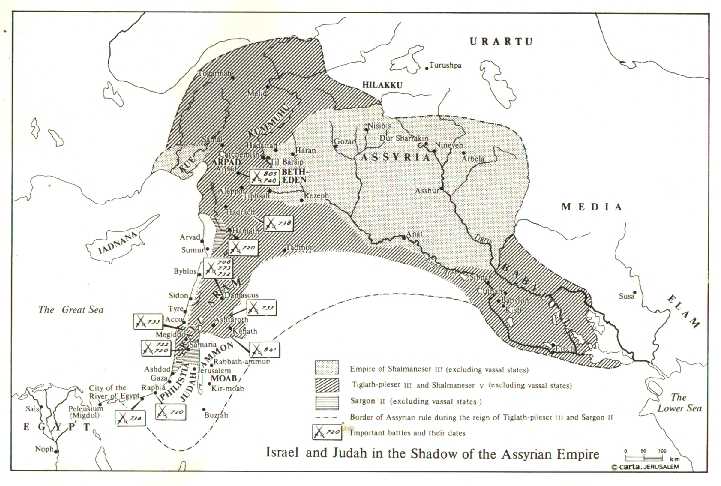

The Assyrian & Babylonian ExilesA significant majority of the Ten Tribes of Israel who constituted the northern Kingdom of Israel during the Biblical Period were taken into captivity by the Assyrians in 721-715 BCE. They were deported to areas adjacent to the place of exile: Media, Assyira and Mesopotamia. This area is roughly what is today called Kurdistan.The Babylonian Nebuchadnezzar II 604-561 BCE inherited the Assyrian Empire. After his war and conquest of Judah, he also exiled many Jews to Babylon. These new exiles, together with the members of the Ten Tribes exiled previously, constituted a large Jewish population. Even when Cyrus permitted their return to Israel, many - especially the wealthy - remained in Babylon. Certain towns, e.g. Nehardea, Nisibis, Mahoza, had an entirely Jewish population, and their position remained favorable during successive regimes. In the 1st century BCE a Jewish State was set up around Nehardea by two brothers, ANILAI (Anilaos) and ASINAI (Asinaios), and this lasted for many years. The Jews of Babylon (Babylon was an empire which contained Kurdistan) remained in constant touch with the Jews of Israel and even supplied some of their leaders (e.g. Hillel) with arms and supplies. During the Roman occupation, the Babylonian Jews rose against the emperor Trajan, the revolt being bloodily suppressed by his commander, Lucius Quietus (116 CE). Under Persian and Parthian rule, the Jews of Babylon (Kurdistan) enjoyed an extensive measure of internal autonomy, being headed by an Exilarch (Exile Ruler). This ruler was of Davidic descent and was the king's representative. The community was governed by a council of elders. Source: The Standard Jewish

Encyclopedia: Tribes, Lost Ten & Babylon

The Jewish Roots of KurdistanThe history of Judaism in Kurdistan is ancient. The Talmud holds that Jewish deportees were settled in Kurdistan 2800 years ago by the Assyrian king Shalmaneser. As indicated in the Talmud, the Jews were given permission by the rabbinic authorities to allow conversion from the local population. They were exceptionally successful in their endeavor. The illustrious Kurdish royal house of Adiabene, with Arbil as its capital, was converted to Judaism in the course of the 1st century BCE, along with, it appears, a large number of Kurdish citizens in the kingdom (see Irbil/Arbil in Encyclopaedia Judaica).The name of the Kurdish king Monobazes (related etymologically to the name of the ancient Mannaeans), his queen Helena, and his son and successor Izates (derived from yazata, "angel"), are preserved as the first proselytes of this royal house (Ginzberg 1968, VI.412). [But this is chronologically untenable as Monobazes' effective rule began only in CE 18. In fact during the Roman conquest of Judea and Samaria (68-67 BCE), Kurdish Adiabene was the only country outside Israel that sent provisions and troops to the rescue of the besieged Galilee (Grayzel 1968, 163) - an inexplicable act if Adiabene was not already Jewish]. Many modern Jewish historians like Kahle (1959), who believes Adiabene was Jewish by the middle of the 1st century BCE, and Neusner (1986), who goes for the middle of the 1st century CE, have tried unsuccessfully to reconcile this chronological discrepancy. All agree that by the beginning of the 2nd century CE, at any rate, Judaism was firmly established in central Kurdistan. Like many other Jewish communities, Christianity found Adiabene a fertile ground for conversion in the course of 4th and 5th centuries. Despite this, Jews remained a populous group in Kurdistan until the middle of the present century and the creation of the state of Israel. At home and in the synagogues, Kurdish Jews speak a form of ancient Aramaic called Suriyani (i.e., "Assyrian"), and in commerce and the larger society they speak Kurdish. Many aspects of Kurdish and Jewish life and culture have become so intertwined that some of the most popular folk stories accounting for Kurdish ethnic origins connect them with the Jews. The tombs of Biblical prophets like Nahum in Alikush, Jonah in Nabi Yunis (ancient Nineveh), Daniel in Kirkuk, Habakkuk in Tuisirkan, and Queen Esther and Mordechai in Hamadân, and several caves reportedly visited by Elijah are among the most important Jewish shrines in Kurdistan and are venerated by all Jews today. Further Readings and Bibliography: Encyclopaedia Judaica, entries on Kurds and Irbil/Arbil; Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, 5th cd. (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1968); Jacob Mann, Texts and Studies in Jewish History and Literature, vol. I (London, 1932); Yona Sabar, The Folk Literature of the Kurdistani Jews (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982); Paul Magnaretta, "A Note on Aspects of Social Life among the Jewish Kurds of Sanandaj, Iran," Jewish Journal of Sociology Xl.l (1969); Walter Fischel, "The Jews of Kurdistan," Commentary VIII.6 (1949); Andre Cuenca, "L'oeuvre de I'Aflance Israelite Universelle en Iran," in Les droits de I'education (Paris: UNESCO, 1960); Dina Feitelson, "Aspects of the Social Life of Kurdish Jews," Jewish Journal of Sociology 1.2 (1910); Walter Fischel, "The Jews of Kurdistan, a Hundred Years Ago," Jewish Social Studies (1944); Solomon Grayzel, A History of the Jews (New York: Mentor, 1968); Paul Kahle, The Cairo Geniza (Oxford, 1959); Jacob Neusner, ludaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism in Talmudic Babylonia (New York; University Press of America, 1986). Source: http://www.kurdish.com/kurdistan/religion/judaism.htm

Kurdistan the Birthplace of the Babylonian TalmudUnder the rule of the Jewish Queen Shlomis Alexandra (also known as Shlomtzion, the widow of King Yannai, grandson of Judah the Maccabee) 76-66 BCE, and under the advice of her brother Rabbi Shimon ben Shetach, the Pharisees (Rabbinical Jews) split with the Sadducees and other militant Jewish groups. Although the Pharisees opposed Roman rule, they preferred academic study to military revolt.In the years prior to the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, this rift in approach to Rome increased to the point of open conflict with Rome and between the militants themselves. The Hellenists sought to assimilate or appease Rome through adopting its culture. The Pharisees sought to preserve the spiritual heritage of Judaism through academies and study. The Herodians, Sadducees and their Jordanian converts plotted revolt. Even though the first revolt resulted in the destruction of the Temple, there was some recovery. The second revolt under Bar Kochba in 135 CE, however, was utterly crushed by Rome. There was a Jewish majority in Israel for hundreds of years after this, but Israel as a autonomous political entity ceased to exist. After these events, the split became geographical. The militant Jews headed south to Jordan and Southern Arabia, eventually founding the Jewish State of Himyar (the Biblical Sheba) in what is now Saudi Arabia and Yemen, still retaining the name "Iudean" or what has come down to us as "Jews". They practiced a modified form of nationalistic Judaism that was eventually transformed into Islam by the Prophet Mohammed. The Rabbinic Jews moved first east, then north and eventually to Babylon. Even after crushing the various Judean revolts, the Romans allowed the Pharisees to establish centers of learning in Yavneh (near modern Tel Aviv) and later in the Galilee and Golan heights. The Roman conversion to Christianity under Constantine and its associated intolerance, combined with the military aggressions of the Jews of Southern Arabia led to a series of decrees essentially making Judaism an illegal religion. Babylon, specifically the area near what is now called Kurdistan, provided a safe haven for Rabbinic - but not militant - scholars. The Babylonian Talmud reflects a society preponderantly based agriculture and crafts. They were learned in Jewish Studies and had produced in the past the books of Ezekiel, Daniel and Tobit. At the beginning of the 3rd century CE, Babylon became the main center of Rabbinic studies. Academies were founded by R. Samuel at Nehardea and by Rav at Sura. In the later 3rd century, the academy of Pumpedita was founded to replace that at Nehardea (destroyed in 261 CE). The importance of these communities was further enhanced with the abolition of the Israeli Patriarch (Local Ruler) in 425 CE, when Babylon became the spiritual center for all Jewry. Chart: A History of the

Jewish People, by H.H. Ben-Sasson, p381

Islamic Conquest and the Babylonian Jewish CommunityPersecutions in the 5th century CE led to the Jewish revolt under Mar Zutra II. This leader held out for 7 years, but was finally captured and killed. The development of the Talmud was discontinued about this time. The position of Jews continued to be difficult until the Arab conquest (7th century). When the Arab conquest began in 637 CE, the large and ancient Jewish and convert community of Kurdistan favored and even assisted the Arab advance in the hope that it would afford them deliverance from Sassanid persecution. Shortly after the Arab occupation some Jews expelled from the remains of the Jewish State in Himyar (what is now Saudi Arabia) settled in Kufa.The Jews were forced to convert by a series

of discriminatory laws applied over the course of two centuries.

They suffered from the restrictions laid down by OMAR, and were excluded

from public office. Having no representation in government, unable

to build any new schools or synagogues, subject to special taxes and occasional

outbursts of religious violence -- the peasant community largely converted

by the end of the 9th century. Because of heavy taxation on cultivated

land, a unique change occurred in the Jewish community. For the first

time a small minority of Jews left agriculture and concentrated in the

larger towns, especially Baghdad, Basra and Mosul where they became traders

and craftsmen. The peasants, however, intermarried and became the

core of what we call today "The Kurds".

Saladin al AyyubiWhen slah al-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub was born in 1138 to a family of Kurdish adventurers in the ( now Iraqi ) town of Takrit, Islam was a confusion of squabbling warlords living under a Christian shadow. A generation before, European Crusaders had conquered Jerusalem, massacring its Muslim and Jewish habitants. The Franks, as they were called, then occupied four militarily aggressive states in the Holy Land. The great Syrian leader Nur al-Din predicted that expelling the invaders would require a holy war of sort that had propelled Islam's first great wave half a millennium earlier, but given the treacherous regional crosscurrents, such a united front seemed unlikely.Saladin got his chance with the death, in 1169, of his uncle Shirkuh, a one-eyed, overweight brawler in Nur al-Din's service who had become the facto leader of Egypt. A seasoned warrior despite his small stature and frailty, Saladin still had a tough hand to play. He was a Kurd (even then a drawback in Middle Eastern politics), and he was from Syria, a Sunni state, trying to rule Egypt, a Shiite country. But a masterly 17-year campaign employing diplomacy, the sword and great good fortune made him lord of Egypt, Syria and much of Mesopotamia. The lands bracketed the Crusader states, and their combined might made plausible Nur al-Din's dream of a Muslim-Christian showdown. Ed Note: Many oriental Jews fought alongside the Moslems to repulse the crusaders. He conquered Jerusalem, and it became even more central to the faithful. Saladin's family ruled less than 60 years longer, but his style of administration and his humane application of justice to both war and governance influenced Arab rulers for centuries. His tolerance was exemplary. He allowed Christian pilgrims in Jerusalem after its fall. The great Jewish sage Maimonides was his physician. Ed Note: He allowed Jews to flourish in Jerusalem and is credited for discovering the Western Wall of the Jewish Temple after being buried by garbage under years of Roman-Byzantine rule. Source: http://www.krds.net/saladin.htm "The Genetic Bonds Between Kurds and Jews" by Kevin Alan Brook Kurds are the Closest Relatives of Jews In 2001, a team of Israeli, German, and Indian scientists discovered that the majority of Jews around the world are closely related to the Kurdish people -- more closely than they are to the Semitic-speaking Arabs or any other population that was tested. The researchers sampled a total of 526 Y-chromosomes from 6 populations (Kurdish Jews, Kurdish Muslims, Palestinian Arabs, Sephardic Jews, Ashkenazic Jews, and Bedouin from southern Israel) and added extra data on 1321 persons from 12 populations (including Russians, Belarusians, Poles, Berbers, Portuguese, Spaniards, Arabs, Armenians, and Anatolian Turks). Most of the 95 Kurdish Muslim test subjects came from northern Iraq. Ashkenazic Jews have ancestors who lived in central and eastern Europe, while Sephardic Jews have ancestors from southwestern Europe, northern Africa, and the Middle East. The Kurdish Jews and Sephardic Jews were found to be very close to each other. Both of these Jewish populations differed somewhat from Ashkenazic Jews, who mixed with European peoples during their diaspora. The researchers suggested that the approximately 12.7 percent of Ashkenazic Jews who have the Eu 19 chromosomes -- which are found among between 54 and 60 percent of Eastern European Christians -- descend paternally from eastern Europeans (such as Slavs) or Khazars. But the majority of Ashkenazic Jews, who possess Eu 9 and other chromosomes, descend paternally from Judeans who lived in Israel two thousand years ago. In the article in the November 2001 issue of The American Journal of Human Genetics, Ariella Oppenheim of the Hebrew University of Israel wrote that this new study revealed that Jews have a closer genetic relationship to populations in the northern Mediterranean (Kurds, Anatolian Turks, and Armenians) than to populations in the southern Mediterranean (Arabs and Bedouins). Source: http://www.barzan.com/kevin_brook.htm

PostscriptIn spite of their conversion to Islam, the Kurds were never accepted as equals to other Islamic groups. Islamic groups constantly feared a revival of the Jewish faith, and several Jewish pseudo-messiahs, such as Abu Issa Al-Isfahani c. 700 and Shabbetai Tzvi 16th CE looked to this community to "raise a Jewish Army to liberate Eretz Yisrael". Islamic end-times theologians saw the former as the model of the "antichrist" Dajjal coming from Isfahan accompanied by 70,000 "Jews". Thus Kurdistan's role as heirs to the Ten Tribes of Israel and a community of immigrants and converts who grew up around the academies of the Babylonian Talmud - the source of non-militant, Rabbinic Judaism of today - was effectively and completely suppressed.This page was produced by Joseph

E. Katz

Offer: "From Time Immemorial" by Joan

Peters, 1984

|

All Rights Reserved