Click for Related Articles

Religious Persecution of Jews by ArabsBefore the Jewish state was

established,

there existed nothing to harm good relations between Arabs and Jews. -- The late King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, November 1973, to Henry Kissinger We are not against the Jews.

Contrary to the myth that Jews lived in harmony with the Arabs before the Zionist state, innumerable authoritative works document decisively the subjugation, ppression, and spasmodic anti-Jewish eruptions of violence that darkened the existence of the Jews in Muslim Arab countries. In truth, before the seventh-century advent of the Prophet Muhammad and Islam, Jews and Arabs did have harmonious relations, and words of praise regarding the noble virtues of the Jews may be found in ancient Arab literature.1 Before the Arab conquest, in fact, some rulers of Arabia "had indeed embraced Judaism," as Muslim historians attest. The Koran itself has been witness to the Jewish nature of the "Israelite communities of Arabia": Koranic references appear about the rabbis and the Torah which they read, and the prestige and reverence with which the earlier community viewed them.2 The Koran contains so many legends and theological ideas found in Talmudic literature that we are able to draw a picture of the spiritual life of the Jews with whom Mohammad must have come into contact.3 It was the Prophet Muhammad himself who attempted to negate the positive titage of the Jew that had been prevalent earlier. According to historian Bernard Lewis, the Prophet Muhammad's original plan had been to induce the Jews to adopt Islam;4 when Muhammad began his rule at Medina in A.D. 622 he counted few supporters, so he adopted several Jewish practices-including daily prayer facing toward Jerusalem and the fast of Yom Kippur-in the hope of wooing the Jews. But the Jewish community rejected the Prophet Muhammad's religion, preferring to adhere to its own beliefs, whereupon Muhammad subsequently substituted Mecca for Jerusalem, and dropped many of the Jewish practices. Three years later, Arab hostility against the Jews commenced, when the Meccan army exterminated the Jewish tribe of Quraiza.5 As a result of the Prophet Muhammad's resentment, the Holy Koran itself contains many of his hostile denunciations of Jews6 and bitter attacks upon the Jewish tradition, which undoubtedly have colored the beliefs of religious Muslims down to the present. Omar, the caliph who succeeded Muhammad, delineated in his Charter of Omar the twelve laws under which a dhimmi, or non-Muslim, was allowed to exist as a "nonbeliever" among "believers." The Charter codified the conditions of life for Jews under Islam -- a life which was forfeited if the dhimmi broke this law. Among the restrictions of the Charter: Jews were forbidden to touch the Koran; forced to wear a distinctive (sometimes dark blue or black) habit with sash; compelled to wear a yellow piece of cloth as a badge (blue for Christians); not allowed to perform their religious practices in public; not allowed to own a horse, because horses were deemed noble; not permitted to drink wine in public; and required to bury their dead without letting their grief be heard by the Muslims.7 As a grateful payment for being allowed so to live and be "protected," a dhimmi paid a special head tax and a special property tax, the edict for which came directly from the Koran: "Fight against those [Jews and Christians] who believe not in Allah ... until they pay the tribute readily, being brought low."8 In addition, Jews faced the danger of incurring the wrath of a Muslim, in which case the Muslim could charge, however falsely, that the Jew had cursed Islam, an accusation against which the Jew could not defend himself Islamic religious law decreed that, although murder of one Muslim by another Muslim was punishable by death, a Muslim who murdered a non-Muslim was given not the death penalty, but only the obligation to pay "blood money" to the family of the slain infidel. Even this punishment was unlikely, however, because the law held the testimony of a Jew or a Christian invalid against a Muslim, and the penalty could only be exacted under improbable conditions-when two Muslims were willing to testify against a brother Muslim for the sake of an infidel.9 The demeanment of Jews as represented by the Charter has carried down through the centuries, its implementation inflicted with varying degrees of cruelty or inflexibility, depending upon the character of the particular Muslim ruler. When that rule was tyrannical, life was abject slavery, as in Yemen, where one of the Jews' tasks was to clean the city latrines and another was to clear the streets of animal carcasses-without pay, often on their Sabbath. The restrictions under Muslim law always included the extra head tax regardless of the ruler's relative tolerance. This tax was enforced in some form until 1909 in Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Turkey; until 1925 in Iran; and was still enforceable in Yemen until the present generation. The clothing as well as the tax and the physical humiliation also varied according to whim. Thus, in Morocco, Jews had to wear black slippers,10 while in Yemen, Jewish women were forced to wear one white and one black shoe.11* [* The edict set by the Sultan of Morocco in 1884 varies somewhat, as did most interpretations of the dhimma law. His restrictions also included insistence that Jews work on their sacred day of rest; carry heavy burdens on their backs; work without pay; clean foul places and latrines; part with merchandise at half price; lend beasts of burden without payment; accept false coinage instead of negotiable currency; take fresh skins in return for tanned hides; hold their beds and furniture at the disposal of government guests, etc.] Jews were relegated to Arab-style Jewish ghettos -- hara, mellah, or simply Jewish Quarter were the names given the areas where Jews resided -- recorded by travelers over the centuries, as well as by Jewish chroniclers. A visitor to four-teenth-century Egypt, for example, commented in passing12 on the separate Jew-quarter, and five hundred years later another visitor in the nineteenth century verified the continuation of the separated Jewish existence: "There are in this country about five thousand Jews (in Arabic, called 'Yahood'; singular, 'Yahoodee'), most of whom reside in the metropolis, in a miserable, close and dirty quarter, intersected by lanes, many of which are so narrow as hardly to admit two persons passing each other in them."13 In 1920, those Jewish families in Cairo whose financial success had allowed them out of the ghetto, under relatively tolerant rule, had been replaced by "poor Jewish immigrants." Thus, although the character of the population may have changed, the squalor and crowding remained. As one writer, a Jew, observed: Our people are crowded and clustered into houses about to collapse, in dark cellars, narrow alleys and crooked lanes choked with mud and stinking refuse, earning their meagre living in dark shops and suffocating workshops, toiling back to back, sunscorched and sleepless. Their hard struggle for existence both inside and outside the home is rewarded by a few beans and black bread.14Under no circumstances were Jews considered truly equal. Among the Jews in Arab lands were many individual personal successes and regionalized intermittent prosperity, but the tradition of persecution was characteristic throughout most of Jewish history under Arab rule.15 If the dhimmi burdens were light in one particular region, the Jew had the residue of fear left from the previous history of pogroms and humiliations in his area. These harsh and ancient dhimma restrictions persisted even up to the present time to some degree, in some Arab communities, and their spirit -- if not their letter -- continued generally throughout the Arab world.16 Throughout the centuries, the Jews were the first to suffer persecution in times of economic turmoil or political upheaval,17 and the cumulative effect of the sporadic mass murders left their mark on the Jews even in periods of relative quiescence. In Syria, the infamous blood libel of 1840 brought about the death, torture, and pillage of countless Jews falsely accused of murdering a priest and his servant to collect the blood for Passover matzoth!18 Before the Jews were finally vindicated of this slander, word of the charges had spread far from Damascus, causing terror in numerous Jewish communities. The scurrilous blood libel has not been purged from Arab literature, however. In fact, the Arabs seem in the past two decades to have seized upon this primitive old calumny with renewed vigor. In 1962 the UAR (Egyptian) Ministry of Education published "Human Sacrifices in the Talmud" as one of a series of official "national" books. Bearing on its cover the symbol of the Egyptian Institute for Publications, this modem book is a reprint of an 1890 work by a writer in Cairo.19 In the introduction, the editor shares his discovery: "conclusive evidence ... that this people permits bloodshed and makes it a religious obligation laid down by the Talmud." The editor's description becomes more vile as it purports to become more explicit regarding the "Indictment."20 Two years later, in 1964, a professor at the University of Damascus published his own affirmation of the nineteenth-century blood libel, stating that the wide attention given the story served a valid purpose: to wam mothers against letting their children out late at night, "lest the Jew ... come and take their blood for the purpose of making matzot for Passover."21 Still another version, also published in the 1960s, "The Danger of World Jewry to Islam and Christianity," alleges that thousands of children and others disappear each year, and all of them are victims of guess who?22 They've even dramatized the infamous canard for the theater. In November 1973, a former minister in the Egyptian Foreign Service published a play based on the 1840 blood libel in Damascus-replete with gory descriptions-in a widely circulated Egyptian weekly.23 During the same month the late Saudi Arabian King Faisal stressed the importance of the blood libel of 1840 in Damascus as a requisite to understanding "Zionist crime."24 And in 1982, shortly after Israel transferred its much coveted Sinai territory to Egypt for a more coveted peace, the Egyptian press (govemment-run) dredged up inflammatory variations on the horrible theme. Two examples: ". . . The Israelis are Israelis and their favorite drink is Arab blood... ."25 and "A Jew ... drinks their blood for a few coins."26 The departure of European colonists in the twentieth century brought into being a highly nationalistic group of Arab states, which increasingly perceived their Jews as a new political threat.* The previous Arab Muslim ambivalence -- an ironic possessive attitude toward "their" Jews, coupled with the omnipresent implementing of the harsh dhimma law -- was gradually replaced by a completely demoniacal and negative stereotype of the Jew. Traditional Koranic slurs against the Jews were implemented to incite hostility toward the Jewish national movement. The Nazi anti-Semitism in the 1930s and 1940s flourished in this already receptive climate. [* The Arab reaction seems not dissimilar to that of a Ku Klux Klansman in the United States, responding vehemently to the question I once asked about his attitude toward integration: "They're our 'Niggers,' and we've taken good care of'em, but I'll be damned if I'll let 'em take over.... Our 'Niggers' don't really wanna vote, y'know." (The epithet is his.) Chicago Daily News, April 10, 1965.] Although Arabs themselves frequently speak of "anti-Semitism" as synonymous with anti-Jewishness -- before the 1947 partition, for example, Egyptian UN Representative Haykal Pasha warned the General Assembly that partition would bring "anti-Semitism" worse than Hitler's27 -- frequently they justify or obscure an anti-Jewish action by saying, "How can I be anti-Semitic? I'm a Semite myself." According to Professor S. D. Goitein, "the word 'semitic' was coined by an l8th-century German scholar, concerned with linguistics.... The idea of a Semitic race was invented and cultivated in particular in order to emphasize the inalterable otherness and alien character of the Jews living in Europe."28 Another eminent Arabist, Bernard Lewis, dates the invention of the term "anti-Semitism" to 1862, although "the racial ideology that gave rise to it was already well established in the early 19th century. Instead of -- or as well as -- an unbeliever ... the Jew was now labeled as a member of an alien and inferior race... "29] As early as 1940 the Muffi of Jerusalem requested the Axis powers to acknowledge the Arab right "to settle the question of Jewish elements in Palestine and other Arab countries in accordance with the national and racial interests of the Arabs and along lines similar to those used to solve the Jewish question in Germany and Italy."30* [* For a discussion of Jewish-Arab relations in Palestine, see The Myth of Palestinian Nationalism, narrowly defined, anti-Semitism] Hitler's crimes against the Jews have frequently been justified in Arab writings and pronouncements. In the 1950s, Minister Anwar Sadat published an open letter to Hitler, hoping he was still alive and sympathizing with his cause. Important Arab writers and political figures have said Hitler was "wronged and slandered, for he did no more to the Jews than Pharaoh, Nebuchadnezzar, the Romans, the Byzantines, Titus, Mohammed and the European peoples who slaughtered the Jews before him." Or that Hitler wanted to "save ... the world from this malignant evil..." 31 Arab defense of the Nazis' extermination of the Jews has persisted: prominent Egyptian writer Anis Mansour wrote in 1973 that "People all over the world have come to realize that Hitler was right, since Jews . . . are bloodsuckers . . . interested in destroying the whole world which has . . . expelled them and despised them for centuries ... and burnt them in Hitler's crematoria ... one million ... six millions. Would that he had finished it!"32 Mansour alleged at another time that the vicious medieval blood libel was historical truth: "the Jews confessed" that they had killed the children and used their blood; thus he justifies persecution and pogroms of "the wild beasts."33 That article was followed by a "report," after Mansour returned from representing Egypt at the Fortieth International PEN (writers') Conference in 1975 in Vienna. In it, Mansour continued the theme: "The Jews are guilty" for Nazism; ". . . the world can only curse the Jews ... The Jews have only themselves to blame." Mansour was angry that "the whole world" protested "all because" a "teacher" told the Jewish waiter serving him in Vienna that Hitler committed a grave error in not doing away with more of you ....'"34 It was from such a climate that the Jews

had escaped, seeking refuge in Israel.

1. Bernard Lewis, The Arabs in History, 4th rev. ed. (New York, Evanston, San Francisco, London: Harper-Colophon Books, 1966), pp. 31-32; S.D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society, vols. I and 11 (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: 197-1), p. 28; see also H.Z. Hirschberg, The Jews in Islamic Lands, 2nd rev. ed. (Leiden, 1974). 2.S.D. Goitein, Jews and Arabs, Their Contacts Through the Ages, 3rd ed. (New York: Schocken Books, 1974), p. 49. 4.Lewis, Arabs in History, p. 42; also see Norman A. Stillman, The Jews ofArab Lands.- A History and Source Book (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1979), pp. 113-114. For further information and fascinating reading, the Stillman work provides new and in-depth insights into the "Jewish social history in the Arab world, spanning 1500 years," with original translations from Arabic and other languages. 5. Lewis, Arabs in History, p. 45, pp. 38-48. See Chapter 8. 6.See examples in Chapter 4; also see Stillman, The Jews, "Some Koranic Pronouncements on the Jews," pp. 150-151. 7.Andre Chouraqui, Between East and West, A History of the Jews of North Africa, trans. from French by Michael M. Bernet (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1968), pp. 45-46; D.G. Littman, Jews Under Muslim Rule in the Late Nineteenth Century, reprinted from the Weiner Library Bulletin, 1975, vol. XXVIII, New Series Nos. 35/36 (London, 1975), p. 65. 8.The Meaning of the Glorious Koran, Surah IX, v. 29, Mohammed Marmaduke Pickthall, ed. (New York: Mentor Books, 1953). 9.Chouraqui, Between East and West, p. 46. Also see Hayyim Cohen, The Jews of the Middle East 1860-1972 (New York, 1973); S.D. Goitein, Jews and Arabs. 10. World Jewish Congress, The Jews ofFrench Morocco and Tunisia (New York, 1952). 11. Saul Friedman, "The Myth of Arab Toleration," Midstream, January 1970; Goitein, Jews and Arabs, p. 67T 12. Ibn Battuta, Ibn Battuta Travels in Asia and Africa 1325-1354, trans. and selected with introduction and notes by H.A.R. Gibb (London, 1929), p. 125. 13. Edward William Lane, Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians 1833-1835 (London, New York, Melbourne: 1890), p. 512. 14. The visit to Harat al-Yahud, Cairo's Jewish Quarter, was recorded in letters from a journalist in Arabic dated June I I and June 18, 1920, cited by Jacob M. Landau, Jews in Nineteenth Century Egypt (New York, 1969), pp. 30-31. 15. Hayyim J. Cohen, The Jews ofthe Middle East 1860-1972 (Jerusalem, 1973), pp. 1-3. 16. See interviews in Chapter 6. 17. Goitein, Jews and Arabs, pp. 6-7, 87, 88, for examples. 18. Heinrich Graetz, History of the Jews, 5 vols. (New York, 1927), vol. 5, pp. 634-639. 19. By Habib Faris, 1890, original title in newspaper, 1890: "The Cry of the Innocent with the Trumpet of Freedom," originally published in Egyptian newspaper al-Mahrusa, then as 1890 book, Human Sacrifices in the Talmud Book republished in 1962 as one of a series of information pamphlets, "National Books," no. 184, 1962, 164 pages, listed as one of the publications by UAR Ministry of Education, # 393 1, edited by Abd a]-Ati Jalal, introduction dated June 16, 1962. Cited by Y. Harkabi, Arab Attitudes to Israel (Jerusalem, 1971), pp. 270-271. 20. Ibid., cited in Harkabi, Arab Attitudes, p. 271. 21.Abd al-Karim Gharayiba, Suriyyafi al-Qarn al-TosiAshar 1840-1876 (Cairo, 1961-62), p. 47, cited by Moshe Ma'oz, The Image of the Jew in Official Arab Literature and Communications Media (Jerusalem, 1976), p. 21. 22. 'Abdallah al-Tall, The Danger of World Jewry to Islam and Christianity (in Arabic) (Cairo, 1964), p. 104, cited by Harkabi, Arab Attitudes, pp. 273-274. 23. Mustafa Sa'adani, "The Tragedy of Good Father Thomas," Akhir Saah, November 28, 1973, cited by Ma'oz, The Image of the Jew, p. 22. 24. AI-Soyyad, November 29, 1973, as cited by Ma'oz, The Image of the Jew, p. 23. 25."Sanctifying War and Hating Peace," by Salem al-Yamani, Al-Gumhuriya, June 22, 1982. 26."The Arabs and the Jews-Who Will Destroy Whom?" by Dr. Lutfi Abd Al-Azim, AI-Ahram Iktisadi, September 27, 1982. 27. Official Records of the Second Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations. Summary Record of Meetings 25 September-25 November, 1947, p. 185. During the proposed partition of Palestine, in November, 1947, Egyptian Representative in the United Nations General Assembly, Haykal Pasha, declared that "The Arab governments will do all in their power to defend the Jewish citizens in their countries, but we all know that an excited crowd is sometimes stronger than the police. Unintentionally, you are about to spark an anti-Semitic fire in the Middle East which will be more difficult to extinguish than it was in Germany." The Egyptian spokesman's threat made clear that the Arab world has interpreted the term "anti-Semitism" correctly -- in the only sense it has been used historically -as a definition of anti-Jewish attitude and action. Arabs do not, as Egypt's President Sadat and others have occasionally claimed, use it themselves as a term connoting both Arabs and Jews. 28. Goitein, Mediterranean Society, vol. II, p. 283. 29.Bernard Lewis, Islam in History: Ideas, Men and Events in the Middle East (New York: The Library Press, 1973), p. 136. 30. Fritz Grobba, Manner und Machte im Orient (Zurich, Berlin, Frankfurt, 1967), p. 194-197, 207-208. Bernard Lewis notes that "this draft was an Arab request to the Germans, not a German offer to the Arabs." Also see: Jon Kimche, The Second Arab Awakening (London, 1970); L. Hirszowicz, The Third Reich and the Arab East (London, 1966), particularly regarding Mufti's 1937 contact with the Nazis: p. 34. 31. Sadat's letter, AlMusawwar, No. 1510, September 18,1953, cited in D.F. Green, ed., Arab Theologians on Jews and Israel (Geneva, 1976 ed.), p. 87. Quoted also by Gideon Hausner, November 16, 1971, at New York. Also see Harkabi, Arab Attitudes, pp. 276-277, for other examples. 32. Al-Akhbar, August 19, 1973. 33. Akhar Saah, Cairo, April 10, 1974, cited by Ma'oz, The Image of the Jew, p. 22. 34. Akhar Saah, Cairo, December 3, 1975. This page was produced by Joseph

E. Katz

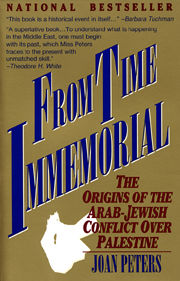

Source: "From Time Immemorial" by Joan

Peters, 1984

|

All Rights Reserved