Click for Related Articles

British Plans against France, and against the Jews in 1915France had to give up claim to Lebanon and Syria by the Arab Revolt's "right of conquest," & on her claim to Palestine by the Jews "right to a homeland" - both ruses to enhance British controlBritish policy in the Middle East was not confined to Palestine. Its purpose, though now a defeated anachronism, informs British attitudes even today. It had its genesis in a historic misrepresentation: the inflation, out of all relation to the reality, of the so-called Arab Revolt during the First World War. This hoax was part of the intricate manoeuvres of the great powers at the end of that war. It was at first directed against France.Early in the First World War, after the defeat at Gallipoli, a group of senior British officials serving in the countries on the fringe of the Ottoman Empire -- in Egypt and the Sudan -- conceived the idea of bringing the vast Arab-speaking areas of the Ottoman Empire under British control after the war. In the words of the then Governor General of the Sudan, Sir Reginald Wingate, they envisaged "a federation of semi-independent Arab States under European guidance and supervision . . . owing spiritual allegiance to a single Arab primate, and looking to Great Britain as its patron and protector."1 The early disaster to British arms in the

Gallipoli Campaign in 1915 provided the impulse. The British government

called on its agents with contacts in the Arab-speaking countries to make

an effort to detach the Arabs from the Turks. The men on the spot in Cairo

and Khartoum decided that Hussein ibn-Ali, Sherif of Mecca, Guardian of

the Moslem Holy Places, a semi-autonomous chieftain in Hejaz (Arabia proper),

was the suitable candidate for levering all the Arabs out of the Turkish

war machine. While London was interested in immediate military relief,

the Arabists in Cairo and Khartoum contrived to, steer and manipulate the

relations with Hussein toward their own more grandiose schemes. Hussein

asked a high price for his participation in liberating his people from

Turkish rule, even at one stage threatening to fight on the side of the

Turks. He demanded all the territory in Asia that had ever been in the

Moslem Empire. He was, of course, employing the accepted Oriental gambit

in a bout of bargaining: he asked for much more than he expected to get.

Moreover the negotiators were warned from London that the British government

had made other commitments in the area, concerning Palestine, Lebanon,

and the Mosul area in Mesopotamia (Iraq). In return for the promise of

liberation in his own territory and the gift of part of the other Arabic-speaking

areas, together with vast sums of money (in gold) and considerable quantities

of arms, Hussein launched his revolt, led in the field by his son Faisal.

British officer named Thomas Edward Lawrence "of Arabia"Toward the end of the First World War, and increasingly after the war, it became common knowledge and part of the popular literature of the age that in the defeat of the Turks a specific and notable part was played by the Arab revolt and that its leaders had enjoyed the indispensable co-operation and advice of a brilliant young British officer named Thomas Edward Lawrence. This revolt, according to the account, began in Arabia, displacing the Turks, spread over into Syria, and reached a climax in the capture of Damascus. In the end, so the story ran, the promises to the Arabs were broken. The Arabs based their later vociferous propaganda -- and their claim to vast additions of territory, including Palestine -- on this account.The major part of this story of the revolt was a fabrication, largely created in Lawrence's imagination. It grew and grew and was not exposed for many years. It suited the makers of British policy at the time so well that Lawrence, who was a yam-spinner of quite extraordinary proportions2 was able to impose himself, and to be imposed, on the British public and on the world, as one of the great heroes and as one of the most brilliant brains of the First World War. Lawrence's monumental book on the subject, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom (of which Revolt in the Desert was an abridged popular edition), was published and publicised and widely accepted as authentic history. In fact, it was largely a work of fiction. On the basis of this fiction, however, the British government was able to initiate and pursue its predominant policy in the Middle East and fight for it in the international arena. Directed at first primarily against France, much of its momentum and later fury was concentrated against the Jewish restoration in Palestine. It was the Lawrence fiction that for many years provided the main propaganda ammunition for the Arabs. The Lawrence legend was finally demolished in 1955 in a remarkable "biographical enquiry" by the British writer Richard Aldington. His findings on the political and military facts were based on an exhaustive study of all the available sources, especially Lawrence’s own copious writings and those he inspired and encouraged. They have been amplified and deepened by the research since made possible by the release of secret British documents of the period. It has consequently become fashionable in Britain today to write with contempt and denigration of Lawrence and to speculate in psychoanalytical overtones on the reasons for his aberrations. Though the myth has been exploded, the

exposure has not yet brought any recognition of the implications, historical

and political, of the myth as a central pillar of British policy. The admission

in Britain of the Lawrence myth is a confession of the tricking of the

French after the First World War and of the falsehoods and fabrications

employed to promote the betrayal of the British trust in Palestine and

of Britain's undertakings to the Jewish people. That betrayal had far-reaching

consequences in fostering and reinforcing the pan-Arab attack on the Jewish

restoration, with all the resultant suffering and bloodshed that continue

to this day.

The aid given to the Allied campaign against the Turks by the Arab Revolt was minor and negligibleThe aid given to the Allied campaign against the Turks by the Arab Revolt was minor and negligible; Lawrence himself, in one of his outbursts of near-penitence, once described it as "a sideshow of a sideshow." Though the Sherif Hussein did send out his call for an Arab rising throughout the Ottoman Empire, in fact no such rising took place. Nor was there a mutiny by Arabs anywhere in the Turkish Army; on the contrary, the Arabs fought enthusiastically in the cause of their Turkish overlords.The operations of the "Arab Army" can be summed up in Aldington's words: "To claim that these spasmodic and comparatively trifling efforts had any serious bearing on the war with Turkey, let alone on the greater war beyond is ... absurd" (p. 209). Aldington further explains that the revolt was limited to the distant Hejaz, an area that was relatively unimportant to the Turks, and to "desert areas close to the British army, from which small raids could be made with comparative immunity. Beyond those areas, where there was real danger to be found and real damage to be done, the Arabs did nothing but talk and conspire" (p. 210). The operations in the Hejaz itself were not conclusive. A few weakly held Turkish positions were taken, but the Turks were not driven out; they held out in Medina for two years. In consequence, "much of the effort of the Arab forces- say 20,000 to 25,000 tribesmen plus the little regular army of 600 ... was diverted to hanging around on the outskirts of Medina and to attacks on that part of the Damascus-Medina railway which was of least importance strategically" (p. 177). These demolition raids on the Hejaz Railway became the most famous operation of the Arab Revolt. Their avowed object was to eliminate the Turkish supply line to Medina, but in fact they did nothing of the sort. Any damage they caused was quickly repaired; its extent was no greater than the damage inflicted on the same railway by the same Bedouin tribesmen in peacetime as part of their customary marauding activities. When General Allenby decided really to put the railway out of commission, he sent British General Dawnay, with a British force, for the purpose; Dawnay demolished it beyond repair. During the final phase of the war, the British conquered southern Palestine. The prospect of victory over the Turks appeared over the horizon. Soon there would be an accounting of what had and what had not been achieved, and by whom. Now, therefore, came the last fantastic phase of the "Revolt." Allenby's great breakthrough in September

1918 provided [the Arabs] with sitting targets which nobody could miss,

and the chance to race hysterically into towns which they claimed to have

captured after the British had done the real fighting. [Aldington, p. 178]

An agreement between the makers of British policy and their Arab collaborators for British - not French - control of SyriaThere was calculated purpose in this behaviour. It was part of an agreement between the makers of British policy and their Arab collaborators. The Arab Revolt had obviously failed as a major or even a significant enterprise. Outside of Hussein's own area of Arabia, it had not attracted any significant assistance from Arabs. In spite of efforts at persuasion by Faisal and Lawrence, the tribes of Syria had refused to join the war effort. No Arab had risen even in the rear of the advancing British troops in southern Palestine. The Hejaz regular force was numerically insignificant, and the Bedouin tribesmen, traditionally well versed in the primitive techniques of looting forays, could contribute nothing to Allenby's offensive through Palestine and Syria. The discussion on the future of the area thus threatened to remain a dialogue between Britain and France, who had reached agreement earlier on the division of the spoils.Herein lay the British dilemma. French control of part of the area, to which London had previously agreed, ruled out the later plan by Cairo and Khartoum for British control of the whole area. Thus the objective of British policy now became to find a way to "biff the French out of all hope of Syria" (in Lawrence's words) or, in the blunter terms used -- disapprovingly -- in the British Cabinet by Lord Milner, "to diddle the French out of Syria."3 This could only be done, if at all, by establishing a plausible Arab claim. In June 1918, an ingenious solution was accepted by the British government. Osmond Walrond, an intelligence officer attached to the Arab Bureau in Cairo, read out to "seven Syrians" living in that city a statement in which the British government officially pledged itself to recognise in the areas not yet conquered the "complete and sovereign independence of any Arab area emancipated from Turkish control by the action of the Arabs themselves."4 On this principle Lawrence and the Sherifians

now hastened to operate in order to establish the "facts" they required.

As an Arab historian has summed it up: "Wherever the British Army captured

a town or reduced a fortress which was to be given to the Arabs it would

halt until the Arabs could enter, and the capture would be credited to

them."5 Hence the wild chase that followed

to raise the Arab flag in towns from which the Turks had already been driven

by the British. Dera’a and Aleppo were two such easy conquests. At Damascus,

there was a serious difficulty, and the manoeuvre did not succeed.

The capture of Damascus & installing Faisal as the indigenous king of Syria before the French could objectThe capture of Damascus, the ancient seventh-century capital of the Arab Umayyad dynasty, was to have been the climax of the revolt, installing Faisal as the indigenous king of Syria before the French could object. General Allenby, the British Commander-in-Chief, ordered the officers in command of the combined British, Australian, and French forces advancing on Damascus not to enter the city. It was assumed that the retreat of the Turks could be completely cut off north of the city. Only the Sherifian troops were to be allowed to pass into the city to announce its capture and set up an administration. All this was worked out in advance between the British War Office, Allenby, and Lawrence. Because Faisal's 600 soldiers were not adequate for the required pomp of his entry, one of his Syrian supporters was sent to recruit Druze and Hauranians to march in with what was now called the Northern Arab Army (it was, in fact, the southern contingent gone north).Two unforeseen circumstances upset the plan. The Australian Commander, Brigadier Wilson, finding that he could not cut off the Turks' retreat without entering the city, therefore went in, and so it was to the Australians that Damascus was in fact surrendered.6 Later, a British force under Colonel Bourchier also went in to quell a rising against the British and against the planned installation of Faisal. It was put down only by the application of considerable force. Nevertheless, a Sherifian administration was installed, and the fiction was then promoted that the Arabs had captured Damascus. France had to give up Lebanon and Syria by the Arab Revolt's "right of conquest"From this scramble to claim territory by "right of conquest," Palestine was excluded. No such effort was made by the Sherifian forces on either side of the Jordan. Coming as it did a year after the publication of the Balfour Declaration on the Jewish National Home in Palestine, this restriction underlines the fact that the Arab leaders felt no urge to oppose or obstruct the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine.In Syria, the clash between French claims, accepted by the British in the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1915, and Arab claims, conceived and fostered by the British after 1916, was not finally resolved until 1945. In Palestine, the French effectively gave up their claims as early as 1918.

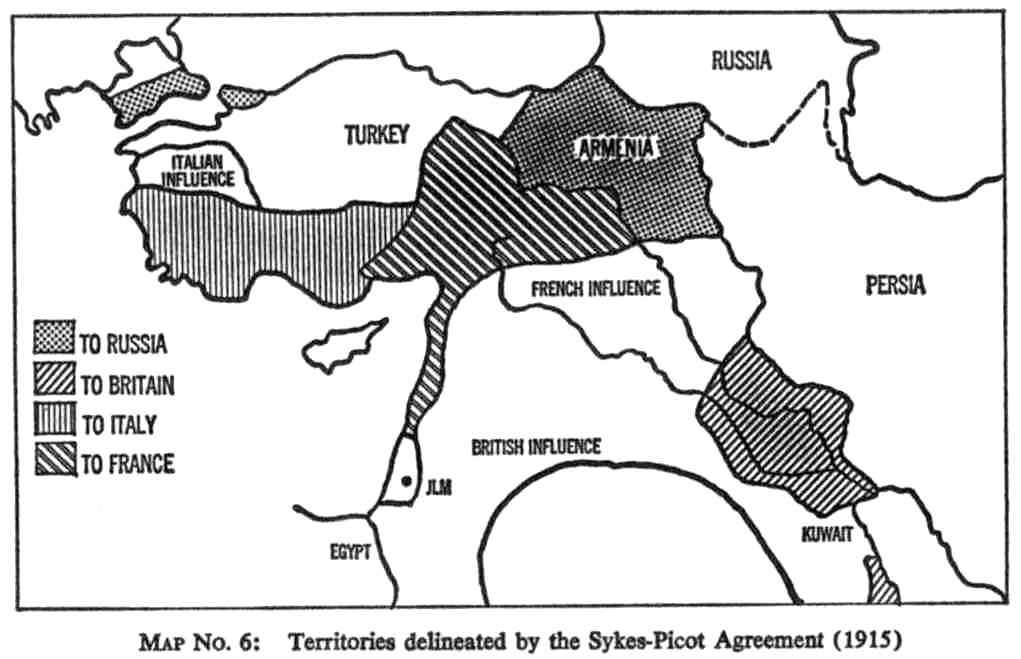

France had to give up on her claim to Palestine by the Jews "right to a homeland", overseen by Britain of courseThe Sykes-Picot Agreement, providing for an international administration in Palestine (see Map No. 6), was the original reason for the exclusion of Palestine from the promises made to Hussein. But in 1917, the British government published the Balfour Declaration for the establishment of the Jewish National Home in Palestine. To achieve this promise of support in the restoration of their ancient homeland, issued after much negotiation and deep consideration, the Jews made a significant contribution to the British war effort. Whatever fantastic interpretations were later put on it, the British intention was clear and was understood clearly at the time. A Jewish state was to be established, not at once, but as soon as the Jewish people by immigration and development became a majority in the still largely derelict and nearly empty country with its then half-million Arabs and 90,000 Jews.This plan would require the tutelage of

a major power. The Mandate system of the then infant League of Nations

seemed to apply perfectly to the situation. British overall control could

be achieved by granting a Mandate to Britain. With a group of Arab states

in Arabia, Syria, and Mesopotamia -- "semi-independent," with British mentors

and advisers in Jedda, Damascus, and Baghdad (not to mention the British-

controlled administration in Cairo and Khartoum) -- and with, now, a British

Mandatory Administration in Palestine, Britain would have unhampered control

of the whole Middle East, from the Mediterranean clear to the borders of

India. Zionist diplomacy was now exploited by the British to achieve the

consent of France to, in effect, her own elimination from any direct influence

in Palestine. This was not an easy matter, especially in view of obvious

British efforts to "biff" her out of Syria as well. The French, however,

were also sensitive during the war to American opinion and had already

acquiesced in the Balfour Declaration. In order to ensure the establishment

of the Jewish National Home, the French agreed, in the end (and not without

some mining and sapping), to waive their claims in Palestine by acceding

to the grant of the Mandate over Palestine to Britain. Considerable pressure

had to be exerted on France over the question of the borders: in the north

she did hold out successfully for the inclusion in "her" zone of the area

enclosing the main water sources of Palestine (which remained largely unexploited).

North-western Galilee was included in Lebanon, and Mount Hermon and the

Golan Heights in Syria.

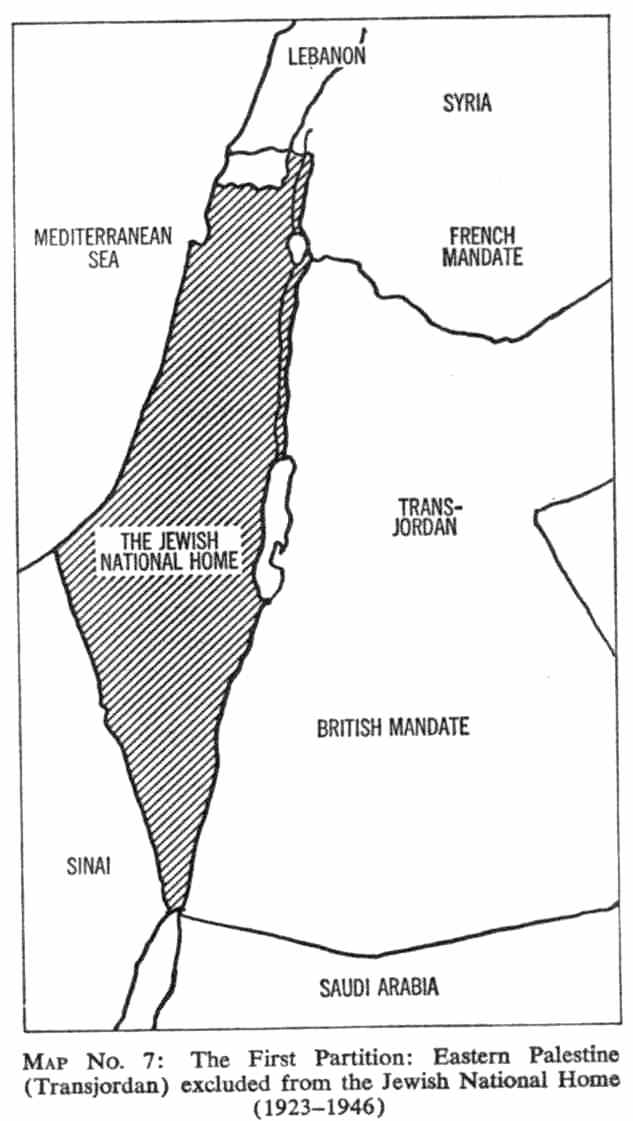

Britain first claimed Jordan would be part of the Jewish Homeland, only to wrest it away from FranceThe claim to eastern Palestine -- Transjordan -- on the other hand was, after a struggle, relinquished by France. Characteristic of the argument brought to bear by the British to persuade her was a leading article in the London Times, in those days an authentic spokesman for the British government. The paper called for the inclusion of eastern Palestine as essential to the Jewish state and urged a "good military frontier" for Palestine to the east of the Jordan River "as near as may be to the edge of the desert." The Jordan, noted the Times on September 19, 1919, "will not do as Palestine's eastern boundary. Our duty as Mandatory is to make Jewish Palestine not a struggling State but one that is capable of a vigorous and independent national life." France consented; eastern Palestine remained part of the area designed for the Jewish National Home and thus passed into British control. A dovetailed Middle East, with Arab client states and a Jewish client state coexisting and co-operating under a completely British umbrella, provided the motive power of official British policy in the period 1917-1920. On December 2, 1917, Lord Robert Cecil had said at a large public meeting in London: "The keynote of our meeting this afternoon is liberation. Our wish is that the Arabian countries shall be for the Arabs, Armenia for the Armenians and Judea for the Jews."7France's claims to Syria and Lebanon upheld by Paris Peace Conference - Faisal, Britain's proxy, ousted from SyriaThe Zionists, moreover, helped the Arabs and the British in the great diplomatic campaign that went on around the Paris Peace Conference and used their influence in Washington to urge the Arab claims. The Emir Faisal was not overstating when he wrote on March 3, 1919, to Felix Frankfurter: "Dr. Weizmann has been a great helper of our cause, and I hope the Arabs may soon be in a position to make the Jews some return for their kindness."France, pressing her claim to Syria and

Lebanon, was granted control over them by the Peace Conference. In defiance

of this decision, a so-called General Syrian Congress offered the throne

of Syria to Faisal; he was subsequently installed in Damascus, where he

set up an administration. The Supreme Allied Council in Paris retorted

by formally granting the Mandate over Syria and Lebanon to France. This

duality could not last. In July 1920, the French ordered Faisal out of

the country.

Faisal wanted Syria, got Iraq, and his brother Abdullah wanted Iraq and got JordanFaisal, bereft of the Syrian crown for which Lawrence and the Arab Bureau had laboured so hard, was instead offered the throne of Iraq by the British, though it had previously been earmarked for Faisal's younger brother Abdullah ibn-Hussein, who was thus left without a throne.At the end of October 1920, Abdullah therefore collected some 1,500 Turkish ex-soldiers and Hejaz tribesmen, seized a train on the Hejaz Railway, and entered eastern Palestine. Here he announced that he was on his way to drive the French out of Syria and called on the Syrians to join him. There was no response, nor was Abdullah given any encouragement by the handful of inhabitants of Transjordan itself. His continued encampment in eastern Palestine

created a dilemma for the British. They had not yet set up any administrative

machinery in what was largely empty territory -- its 90,000 square kilometres

were estimated to hold at most 300,000, inhabitants, most of them nomads.

The British feared, or were induced to fear, that the French, angered by

Abdullah's threats, would invade eastern Palestine. They therefore casually

suggested to Abdullah that he forget about Syria and instead become a representative

of Britain in administering eastern Palestine on behalf of the Mandatory

authority. Whereupon Abdullah generously resigned himself to the French

presence in Syria and took up office in Transjordan, and in time accepted

it as a substitute.

Britain altered the Palestine Mandate to suite its [Arab] needsThe British government then recalled that eastern Palestine was part of the area pledged to the Jewish people. They thereupon inserted an alteration in the draft text of the Mandate (then not yet ratified by the League of Nations), which gave Britain the right to "postpone or withhold" the provisions of the Mandate relating to the Jewish National Home "in the territories lying between the Jordan and the eastern boundary of Palestine as ultimately determined." The Zionist leaders were stunned by this threatened lopping off of three quarters of the area of the projected Jewish National Home; its establishment had, after all, been Britain's warrant for being granted the Mandate. But the British government countered with the proposal that, if the Zionists did not accept the situation, Britain would decline the Mandate altogether and thus withdraw her protection from the Jewish restoration. The Zionist leaders-struggling with the material problem of building a country out of a desert and restoring a people, largely impoverished, from the four corners of the world-were moreover inadequately equipped with political experience to judge the emptiness of the British threat. They did not feel strong enough to resist this blow to the integrity and security of the state-in-building and to their faith in the sanctity of compacts.9

Thus, as a purely British manufacture, filched from the Jewish National Home, torn out of Palestine of which it had always been an integral part, there was brought into being, from the empty waste what subsequently became a spearhead in the "Arab" onslaught on the Jewish state, the Emirate of Transiordan, later expanded across the river and renamed the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (see Map No. 7). The elimination of eastern Palestine in 1921-1923 was only the first act-though stark, dramatic, and momentous-in a developing effort by the British to frustrate and emasculate the Jewish restoration that began in Palestine immediately after the British occupation. At first British policy was confined to the military administration in Palestine itself. In colonial politics, nothing seems to

succeed like repeated error and miscalculation and failure. The Cairo-Khartoum

school of British officials in 1916 had grossly overestimated the influence

of the Sherif Hussein of Hejaz on the Arabs outside his own area. His "revolt"

proved a damp squib and had to be retrieved and embellished by a large

fraud. But these officials did not give up their dream of a large Arab

state or federation of states, extending from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean

and from the borders of Turkey to the southern seaboard of Arabia and supervised

by Britain. It was the men of this school who continued from Cairo to direct

overall British policy for the occupied territory and who came into Palestine

with Allenby or, in the wake of his victory in 1918, to form the military

administration in Palestine. They were stricken to the heart by their government's

deviation from what they had conceived as the correct policy to be followed

in the Fertile Crescent.

Just as the British continued trying to "biff the French out of Syria," they applied themselves to biffing the Zionists out of PalestineBut the Balfour Declaration, the promise of Jewish restoration, even if shorn of its historical sweep, was seen by London as a clear quid pro quo to the Jews for their contribution to Allied victory and as a great moral reason for France's renunciation of her claim. The policy it embodied became the indispensable (or unavoidable) condition for the Mandate being granted to Britain. To the ruling group in Jerusalem -- almost wholly composed of leaders or disciples of the Cairo school -- the Balfour Declaration guaranteeing Jewish restoration represented an intolerable interference in their plans. They set out to undermine it. Just as they continued trying to "biff the French out of Syria," they applied themselves to biffing the Zionists out of Palestine. While their government was still canvassing international support to grant Britain the Mandate in order to implement the Zionist policy, and while the Zionists were urging Britain's claims, the first British administration in Palestine was busily engaged in open defiance of its government’s declared policy.It was this group, all-powerful on the spot, that inspired and mobilised and established organised Arab resistance to the Jewish restoration. It used its power and authority as a military regime to establish facts, to create events, and to control them. It was this group whose views progressively pervaded the subsequent Mandate regime. 1. In a letter to Lord Hardinge, August 26, 1915. Wingate Papers, School of Oriental Studies, Durham University; quoted by Kedourie~ p. 17. 2. The Truth about Lawrence -- the phrase is almost a contradiction in terms," notes the British pro-Arab writer Christopher Sykes. Introduction in Richard Aldington, Lawrence of Arabia, 2nd ed. (London, 1969). 3. Letters of T. E. Lawrence (London, 1938), P. 196; Milner cited in David Lloyd George, The Truth about the Peace Treaties (London, 1936), P. 1047. 4. This document was never published officially but was presumably to be held "available" in case of French reactions. It is quoted by George Antonius, The Arab Awakening (London, 1938), p. 271. (italics added) 5. Muhammed Kurd Ali, Kh1tab el Sham, Vol. III (Damascus, 1925), p. 154, quoted in & Kedourie, England and the Middle East (London, 1956), P. 21. 6. See Kedourie, Chatham House Version, p. 51; Muhammed Xurd Ali, quoted in Chatham House Version, p. 40; W. T. Massey, Allenby's Final Triumph (London, 1920), P. 230. 7. There was indeed close diplomatic co-operation between Armenians and Zionists, especially between Weizmann and Aaron Aaronson on the Zionist side and the Armenians Nubar Pasha and James Malcolm. The efforts failed; the Armenians did not gain their independence. 8. The claim

to eastern Palestine was unanimously reiterated by the Zionist Congress

in 1923 and remained part of the program of the Revisionist Party under

Vladimi (Zeev) Jabotinsky and of the Socialist Achdut Avodah Party.

This page was produced by Joseph

E. Katz

Source: "Battleground: Fact & Fantasy

in Palestine" by Samuel Katz,

|

All rights reserved. Reprinted by Permission.

Portions Copyright © 2001 Joseph Katz